Saints or Sinners?

When it comes to how we understand and respond to history, it’s rarely a simple question to answer.

When demonstrators threw the statue of slave-trader Edward Colston into Bristol harbour in 2020, it showed that monuments can have powerful meanings. For Bristolian families with ancestors who were enslaved in Africa and trafficked to the West Indies, Colston’s statue felt like an insult. Years of discussion about putting a plaque under it to explain Colston’s past had come to nothing and frustration finally boiled over.

A family at the broken plinth of the toppled statue of Edward Colston in Bristol. © Adrian Sherratt / Alamy Stock Photo.

For many of us, statues, street names and public buildings commemorating historical figures are little more than background features. If we consider them at all, we see them as remnants of a distant past, rather than monuments to people responsible for brutal and inhumane acts. The explosion of fury over Colston shows that we need to acknowledge our complex history and find new ways of understanding and representing it.

Wales and slavery

The Atlantic slave trade of the 16th-19th centuries, where entire populations were uprooted and traded as commodities, is now recognised internationally as a crime against humanity. Wales did not stand apart from this abuse. Welsh mariners and investors took part in the slave trade and Welsh people invested in slave-worked plantations. Welsh trades and industries made cloth, copper and iron for markets that were dependent on slavery in Africa and the Caribbean, and Welsh consumers bought tobacco, coffee and sugar grown by enslaved people.

It may have been hard to avoid participating in the economies created by slavery and colonialism, but it’s important to examine the commemoration of some of those directly responsible.

Complicated stories

Statues tend to make heroes of people, but it’s not always helpful to think in absolute terms of heroes and villains, saints and sinners. Social attitudes and commonly held opinions can change hugely over time, and many figures have complex histories that need careful consideration. Some may, in due course, be viewed more sympathetically than others.

For example, Cardiff Institute for the Blind founder Frances Batty Shand was a philanthropist and Jamaican woman of colour – as well as someone who profited from plantations run with slave labour. Some people both defended West Indian interests and supported emancipation, including the widely commemorated prime ministers Wellington and Gladstone.

A challenging case is that of Robert Owen, justly remembered for his pioneering ideas about working. While he sought improved conditions for British workers, he suggested that enslaved people would be better off without emancipation. He shows that even progressive thinkers can be blinkered by the norms of their era.

Statue of Robert Owen in Newtown, Powys. © Powys Photo / Alamy Stock Photo.

Looking further

In order to better understand how Wales’ complicated history is represented today, in July 2020 the First Minister commissioned an audit of public monuments, street and building names associated with the slave trade and the British Empire. It lists plaques, statues and other monuments commemorating historical figures with potential links to slavery.

By contrast, the audit discovered just seven commemorations of people of Black heritage in nine separate locations, including plaques to Paul Robeson and a Mandela Avenue in Bridgend. People of Black heritage have lived in Wales for 2,000 years and made distinguished contributions in politics, education, sport, the arts, health and other spheres, so there is scope to commemorate many more inspiring individuals.

Celebrating Black history

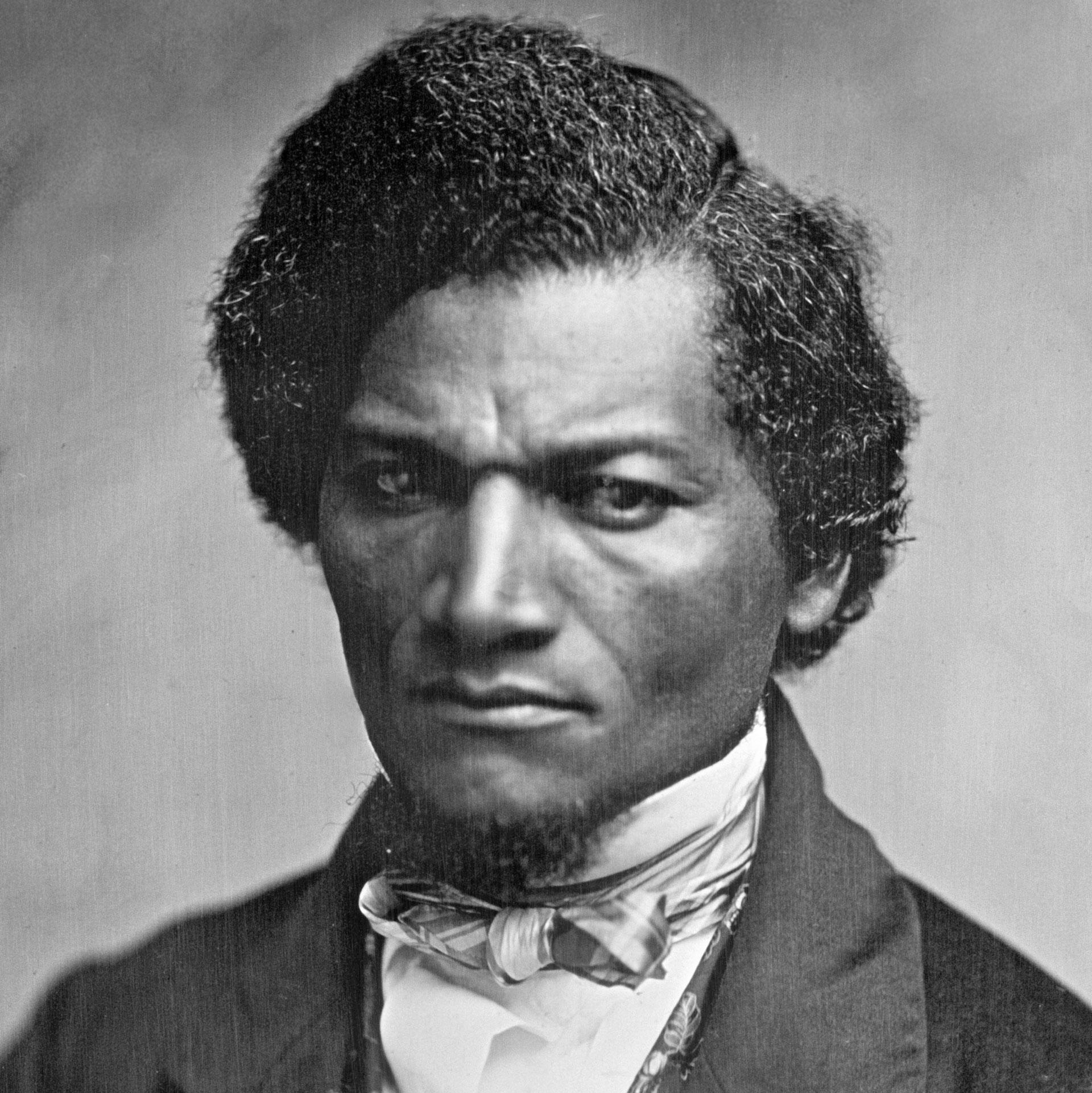

There’s Eddie Parris, who in 1931 became the first Black football player capped for Wales, the diplomat Abdulrahim Abby Farah from Barry who set up a hospital for landmine victims in Somalia, or the anti-slavery orator Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery in America and spoke to a packed Wrexham Town Hall in 1846.

Frederick Douglass. © Major Acquisitions Centennial Endowment.

Work to recognise these individuals, and many more like them, is part of a wider reappraisal of our past. Commemorations are just one part of a long history of changing attitudes but also a rich territory in which to remember, challenge and evolve.

(This is an edited version of an article previously featured in Cadw members' Heritage in Wales magazine).