Paul Robeson’s Wales

Despite a string of iconic roles on stage and screen during the first half of the 20th century, American singer, actor and activist Paul Robeson is better remembered in Wales than in his home country.

The sound of music

According to legend, Robeson was walking home after performing in the musical Show Boat on London’s West End in 1928 when he heard a choir singing in the street. The singers were unemployed Welsh miners who had marched to London to protest about poverty and destitution in the South Wales valleys. Robeson spontaneously joined them, lending his astounding bass-baritone voice to their ranks. It marked the start of a long friendship with the Welsh working class, who found an unlikely champion in the black movie star from New Jersey.

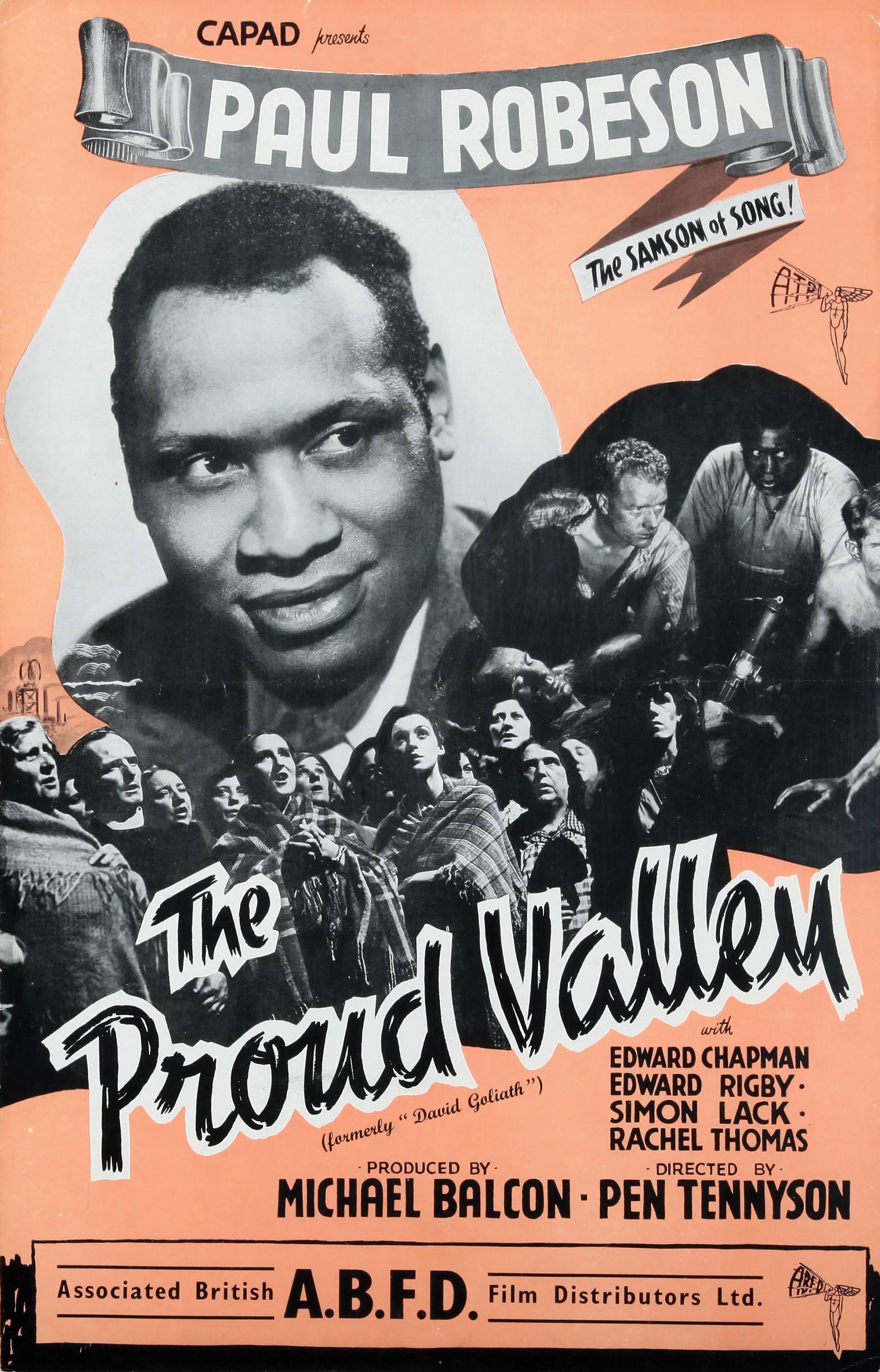

The Proud Valley. © Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

This scene was echoed in The Proud Valley, released in 1940 and filmed in Llantrisant, Tonyrefail and Cwm Darran. Robeson plays a black American sailor (the strikingly named David Goliath) who docks in Cardiff and looks for work in the Valleys, where he is quickly adopted by miners keen to add him to their male voice choir. In the film, Robeson’s character encounters just one episode of racism from a fellow miner, his friends defending him with the line ‘Aren’t we all black down that pit?’. Unfortunately, in real life, things were never that easy for black Welsh miners.

The Proud Valley, 1940. © South Wales Miners' Library. People’s Collection Wales.

Part of the community

As well as performing across Wales in the 1930s, Robeson gave generously to local communities. On 22 September 1934 he was performing at the Llandudno Pier Pavilion when news broke of an explosion at Gresford Colliery near Wrexham. Hearing of the disaster, Robeson made a large donation to the families of the 266 men who lost their lives.

Robeson also donated to the Talygarn convalescent home near Llantrisant. This grand mansion was built around 1880 for the industrialist G.T. Clark before being sold to the South Wales Miners’ Welfare Committee in 1922. Alongside the treatment that thousands of injured miners received in the house and gardens, they also enjoyed private performances from Robeson himself.

Both the site of the pier pavilion and the Talygarn convalescent home are now protected as Listed Buildings.

Giving something back

In the 1950s, the Welsh had an opportunity to repay some of Robeson’s generosity. As the Cold War developed between the USA and the USSR, he was caught up in the paranoid hunt for Communist spies. Robeson was banned from performing and his passport was cancelled, stranding him in the USA. The Welsh communities he had helped took a leading role in the international ‘Let Paul Robeson Sing!’ campaign and petitioned the US Supreme Court on his behalf.

In 1957, still unable to travel, he sang down the telephone line to a packed house of 5,000 people in the Porthcawl Pavilion for the Miners’ Eisteddfod. The listed theatre now has a ‘Paul Robeson Room’ in his honour, as does the Park and Dare Theatre, home of Treorchy Male Voice Choir who also performed at the Eisteddfod.

National Eisteddfod, Ebbw Vale 1958. © South Wales Miners' Library. People’s Collection Wales.

On the frontline

At the Porthcawl concert, Robeson was introduced by Will Paynter, the President of the South Wales Miners Federation and a veteran of the Spanish Civil War. When fascist generals led a coup against the elected government of Spain, hundreds of volunteers from Wales fought to defend Spanish democracy. In 1938 Paul Robeson sang to these troops on the front lines. Later, at the Welsh National Memorial Meeting to the 33 Welshmen killed in the war, he said ‘These fellows fought not only for Spain, but for me and the whole world.’ The memorial meeting was held at the Mountain Ash Pavilion, which was demolished in 2007.

Spanish civil war memorial. © Crown Copyright 2022.

Family connections

Robeson often visited his uncle, Aaron Mossell who lived in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay for over 20 years. In the 1930s, Mossell campaigned against racist councillors in Cardiff and for fairer pay for black sailors. The docks of Cardiff Bay are listed structures, but little remains of the homes of the sailors and port workers. Mossell’s home in Loudon Square was bulldozed in the 1960s and replaced with the Loudon and Nelson tower blocks.

Robeson on an anti-segregation march 1948. © South Wales Miners' Library. People’s Collection Wales.

The Wales Paul Robeson knew and loved, of coal mines, music halls and Tiger Bay has mostly disappeared. But if he were to visit Wales today, he would still recognise places such as Talygarn, Cardiff docks, Porthcawl Pavilion and some of the listed relics of the coal industry.

You can explore what heritage is protected in your own area by visiting Cadw’s online, interactive map, Cof Cymru which includes information on the historic monuments associated with other influential black people from Wales’ past.

(This is an edited version of an article previously featured in Cadw members' Heritage in Wales magazine).

Black history in Wales

Here are some other famous figures in Welsh history and the listed monuments associated with them.